/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13742118/TUA_101_Unit_00831.jpg) |

| Adorable shorts are cool. (Change my mind.) |

It turns out 2019 was quite the year for dramas based on comic books. On the big screen we saw Disney's MCU series finally come to a gorgeous, decades-long climax with

The Umbrella Academy

Tweenage superheroes in goofy prep-school uniforms (including kinky eye-masks, Argyle sweaters, knee-length socks and adorable little shorts) ought to be a genuinely fun idea. X-Men go full Hogwarts? Why not? Mix in time-travelling men in black assassins from Doctor Who (or at least from the 1990s "wilderness years" novels and comics versions of the franchise) and you should almost by definition have a kick-ass (if not quite Kick-Ass) comic book and a very serviceably fun but fucked-up TV show.

So! Did it work?

Well I've never read the comic, so I can't possibly say whether the Netflix people did a good job of adapting the source material. As a show though it's... OK. As I said, the main gimmick is sound, being mostly tried and tested, and the back-up time travel gimmick has of course been tried and tested to destruction (even if I use the phrase advisedly).

Just as Stan Lee taught us that superheroes can have their human sides, and Watchmen taught us that if Batman were real he'd have more in common with Nathan Bedford Forrest (or at least Bernhard Goetz) than he would with Sherlock Holmes, now we're invited to imagine that not all super schools are quite so "enlightened" as Charles Xavier's. In fact there's nothing like being brought up with your fellow (alien) septuplets in a big house in New York, with an emotionally distant authoritarian Englishman (also an alien though!) for an adoptive father and an android Stepford housewife for a mother and, er, an augmented chimpanzee for a butler to leave you... an angry, embittered, emotionally needy, "dysfunctional", and generally just typically obnoxious millennial. Only with superpowers!

If the X-Men were written to appeal to teenagers not too cool for school but definitely too cool to fight in Vietnam, the Umbrella Academy were evidently supposed to be channeling the angst of a generation that couldn't quite cope with 9/11, Bush and Iraq. Now they've been repackaged in time for the Great Awokening, I'd suggest that updating them by the better part of two decades wasn't such a great idea.

For one thing, they don't really fit into the post-2008 era, let alone the world post-2016. It's hard to sympathise with the marital problems of a super-powered Hollywood celebrity (for example) if you're a 40-year-old man who can't afford to move out of his mother's spare room, and when teenagers are being sacked from university and having their lives ruined for expressing the "wrong" opinions on WhatsApp it's a bit much to suggest they should be angry at their 'rents for having been too strict. (Then again, the total failure of the entire media establishment to come to terms with either the Great Recession or the post-Obama revolutions of Brexit and Trump is an ongoing cultural problem. So perhaps one shouldn't judge Netflix too harshly for failing adequately to adapt a 2000s comic-book to a late 2010s zeitgeist.)

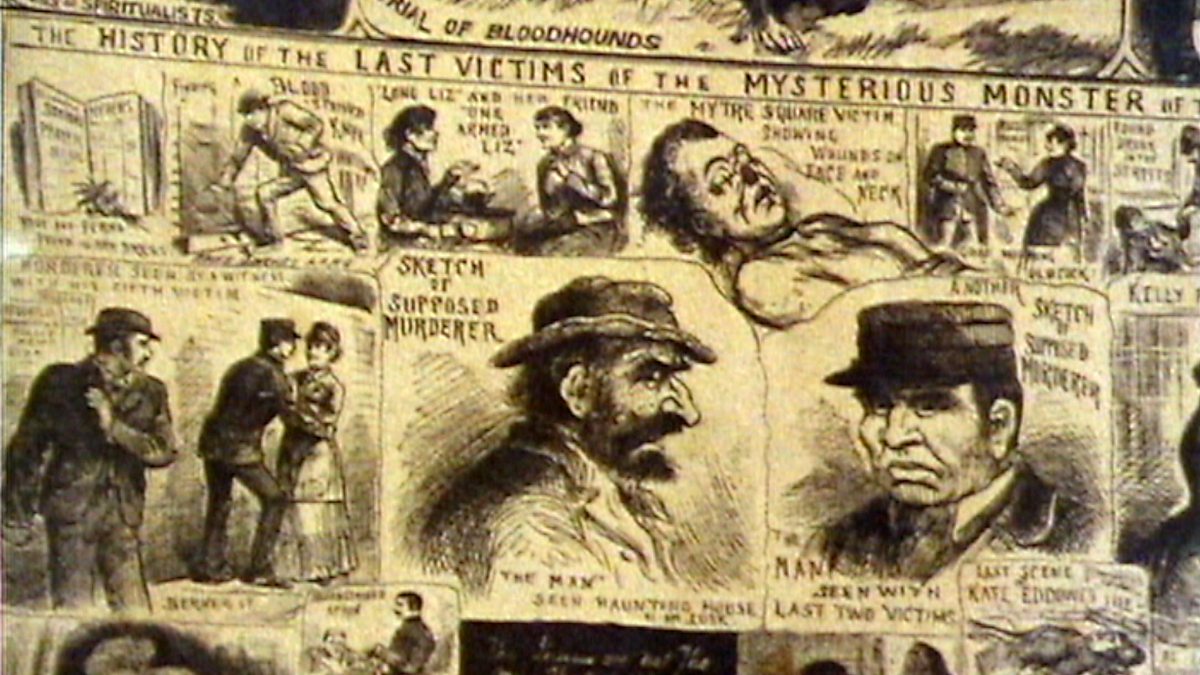

|

| Thomas Hoepker's "most controversial photo" of 9/11 |

Rather more important is that The Umbrella Academy has a very distinct post-9/11 vibe to it. When Mohamed Atta and his chums brought down the World Trade Centre, they also challenged many of the Baby-Boomers' and Generation X's previously devoutly held beliefs (even if in the end they didn't quite manage to bury them). Thomas Hoeopker's infamous photograph in fact illustrated not so much the indifference of young Americans' to their fellow citizens' suffering but their complete inability to comprehend what was going on. "I don't get it, dude. Why would anyone want to attack us? We're cool, aren't we?" Because whereas previously multiculturalism had been seen only as a Good Thing and America's role on the world stage had only ever (or at least since 'Nam) been seen as "a force for good", suddenly young Americans were invited to re-imagine both America's relationship with the world beyond their borders and their own relationship(s) with the American government itself.

Of course, in a comparatively short period of time the fantasies of the past all bounced back in the shape of conspiracy theories about Bush, oil, evangelical Christianity and (of course) racism. But for a short while the kids who'd grown up watching John Hughes movies and listening to the sonic sewage of MTV felt vulnerable both physically and intellectually. Having finished the first season of The Umbrella Academy therefore, I was interested to discover that it was the brainchild of Gerard Way, who was of course (with My Chemical Romance and in particular 'The Black Parade') one of the very, very few creative talents to have tried in any way to come to terms with 9/11 artistically. And whereas 'The Black Parade' was an unusual and (at least in some ways) original reflection on how young people should think about death, the first Umbrella Academy story gives the dysfunctional early 2000s generation their own comic-book avatars, who are supposed to overcome their own dysfunctionality and bickering in order to stop the End of the World.*

Admittedly, it's hard to make dysfunctional people dramatically engaging, let alone sympathetic. There aren't many people in The Umbrella Academy that we can really be expected to root for. But then one presumes that's the point. Deep down, each one of them is a beautiful damaged human being, and in the end they all love each other, and we learn to love them as they reconnect and rediscover what they have in common. Or... something like that.

The only really good thing about the Netflix adaption is of course Aidan Gallagher. Robert Sheehan finishes comfortably but still distantly in second place, playing a gay character who hardly develops at all. (He goes to 'Nam - having travelled back through time to get there - and comes back not significantly affected by the experience beyond having had a boyfriend who then died. Which makes one wonder if that's really all the significance that war can have to a X-gen/millennial audience.) And unfortunately it also has one really, genuinely bad thing going on, and that of course is the abysmal Ellen Page. And it is unfortunate because she's really, really, really bad. She's clearly supposed to be an "interesting" baddy. But alas, she really, really isn't.

And on the subject of interesting baddies, that brings us neatly to...

The Boys

Should one feel disappointed that a TV streaming series called The Boys hardly has any actual boys in it?†

Only joking! The Boys is glorious, and so gloriously fucked-up it should be on one of Russell Brand's 12-point rehab programs.

Simon Pegg gives it a big daddy kiss of approval. In the original comic book he was actually the inspiration for the main character, and he even wrote a foreword to one of the trade paperbacks by way of a wink and a thank-you. Here he literally plays the daddy of the main character, albeit with a slightly ropy Noo Yawk accent. Karl Urban sports an if anything even ropier London accent, though he goes on more or less to save the series on a character level just by projecting sheer scary bear charisma. Less successful is the actual main character, played tolerably but almost entirely without charisma or insight by Jack Quaid, as is his similarly one-dimensional super-powered girlfriend played by Erin Moriarty. (I just had to google their names, so trust me they're forgettable.)

In fact the series titular heroes - a slightly screwy squad of CIA gunslingers who are dedicated to "bringing down" (politically, legally and literally) the world's superheroes (who in general terms are asshole versions of DC's Justice League) - are surprisingly dull. There's a token black man (of course), who believes in Jesus and lies to his wife. There's a comedy token Frenchman (for some reason), who tortures people to death and then fusses about his baguettes and so on. And then there's Karl Urban's character Butcher, who's out for revenge, and we definitely feel his pain, but then he flies into a homicidal rage and murders Haley Joel Osment (whose guest appearance as a psychic washed-up former child prodigy is quite fabulously dark) in a public lavatory.

And that's sort of it for the goodies. Yes, obviously the series was trying to go down the now well trodden GoT route of not really having goodies and baddies. But there's a sense in which that wasn't quite what was wanted. It's clearly supposed to be "challenging", but if one really wanted to challenge modern norms one could easily have flagged up (for example) why a man and a woman who aren't married to each other should think it's OK to fornicate. Quaid's nerd and Moriarty's feisty blonde are supposed to be the goodies, but they're only goodies in that they both have utterly cliched story-arcs. Her "rebel without a clue" arc is even lamp-shaded by the Wonder Woman character. His arc looks as if he might be a new Breaking Bad-type character in the making, but as of the end of the first seasons he's nowhere near there yet. (In the last episode he shouts "Sorry!" whilst murdering private security guards. Is that supposed to be darkly funny? I'm not even sure that it was.)

|

| "Post-modern? Moi?" |

What saves the series rather than the Boys themselves is the baddies, who are of course the not-so-super superheroes. And boy, what wonderful baddies they are! If the X-Men comics humanised heroes and Watchmen and its followers meditated on the dehumanizing effects of having great power and great responsibility, The Boys takes the latter concept one stage further and asks what sort of people superheroes would be in the "real" world of rolling news channels, Hollywood blockbusters and media-savvy politicians.

Obviously the whole world at some point is going to have to come to terms with why we're currently spending the same sort of money at the cinema to see Iron Man thump Thanos as we used to spend on Gone with the Wind (or at any rate on a pseudo-sci-fi Gesamtkunstwerk like Star Wars - or even an American homemade neo-Marxist mythological masterpiece like Titanic). Personally I think there are perfectly legitimate economic reasons why we do. (Patriotic epics are all very well, but by definition they have limited international appeal. And yes, that includes Bondage.) And it's possible that even kiddie wizards and neo-mediaevalism may simply have had their day (especially now that China is opening up to Hollywood). But there's also a clear sense in which the 21st century world has both forgotten the past (the historical epic is currently beyond resuscitation) and lost faith in the future (because sci-fi as a genre isn't much better off), and so it contents itself with a fantastical version of the world of the present day. The question is, does it dare from such a vantage point to say anything about (let alone to) that present-day world. And does it have anything to say?

Like The Umbrella Academy, The Boys does indeed "deal" with 9/11, but having been written by a Brit rather than an actual resident of New York it does so far less obliquely, far more cynically and (arguably) more observantly.†† In fact it has an actual 9/11 calque in the shape of a 'plane hijacking that the heroes then make a hundred times worse when they intervene. And the character who fails to save the day but who then goes on to save virtually the entire show is of course Anthony Starr's Homelander. In the current golden age of television, when writers write to character rather than plot and then write their characters to the actors playing them (even when it means they end up with character-arcs that make no sense in the context of the plot - witness Jaime Lannister and Daenerys for a couple of good examples!) it was perhaps inevitable that having cast somebody really good as their main baddie they would end up whether intentionally or not making him the most "interesting" character of all. Because Anthony Starr, to employ a phrase, absolutely kills it.

Homelander on screen is cleverer, more charming, more three-dimensional, more devious and more ruthless, and altogether more interesting than he was in the comics. Is this just a problem with writing to a genuinely good actor? (And the Great Awokening has certainly sorted the men from, er, the boys in that regard. With fewer white heterosexual roles out there, even a thorough-going scary villain like Homelander, much like Smith in MitHC, will end up becoming a deeply compelling antihero.) He's cynical enough to bring a baby into a room with a bomb just because he wants to know if it will survive the blast - because he wants to know whether it's his or not. And the scene when he finally gets the measure of evil domineering single-mother lipstick-feminist nympho Hillary-clone Madelyn Stillwell and lasers her brain out of her head must have raised a cheer from every God-fearing toxic masculinist throughout the English-speaking world.†††

Umbrella Academy went to town on the idea of superheroes being emotionally immature adults, but The Boys goes all the way to the big city on it. And in doing so it doesn't just dip into a somewhat hackneyed critique of what a liberal American might consider to be a cold-showers boarding school-style of education. Perhaps inadvertently The Boys holds up what a leftist Ulsterman might consider a mirror to America itself. Yes, it turns out that Homelander was brought up in a laboratory. But then "real-life" modern America is itself just as much an artificial being. After all, what other sort of country could ever be satisfied with such an utterly banal version of protestant "Christianity", in which religion is reduced to pop music, scriptural slogans and foreign aid campaigns? (Give me dogmas and incense any day!) In what other sort of country is it considered sexually mainstream for teenage boys to lust over women's mammary glands. (Over here, even straight men prefer their hindquarters.) If America were a superhero it would be Superman, and if Superman were real he'd a smug but neurotic evangelical obsessed with tits.

One final thing that The Umbrella Academy and The Boys have in common is that each breaks with its comic book source by giving its first season a cliffhanger ending, and one indeed that holds out a glimpse of a possible "nostalgic" resolution. The Umbrella Academy's is fairly simple. Even if is about to "get messy", we're still invited to imagine the characters are on the verge of going back through time and having a Quantum Leap-type second chance, with childhood innocence, order and beauty restored. The Boys on the other hand ends with a humdinger of a twist, when we find out that both Butcher's wife and Homelander's son are alive and well and living in a leafy suburb somewhere - though not how any of them will really react to their discovery.

So, have we seen the last of Ellen Page? Will the Umbrella Academy now be able to move on from that quirky, slightly convoluted time-travel story and continue having new wacky adventures for years to come? Will Butcher be able to come to terms with the probability that he was legitimately cuckolded by Homelander and certainly not widowed? Will Homelander give his long-lost son the chance to become the emotionally developed human being he could never be? (Because even being brought up by a single mom beats growing up as a super-powered lab rat.)

With second seasons in the pipeline for both shows, each has plenty to play for.

|

| "No! I am Darth Vader." |

†There is one, as it happens, and he's mouth-watering.

††Having been brought up on legends about Dunkirk, Brits are perhaps more familiar with the ability government spin-doctors have to turn a monumental establishment fuck-up into first a national tragedy, then a national parable, and finally into a foundational myth for whatever the Government wanted to do in the first place. (As a WWII nerd, one suspects Garth Ennis would appreciate the parallel.)

†††They did repeat Brightburn's goof though - i.e. when Superman's heat vision blasts straight through the back of your skull it's unlikely you'll have time to wince and say "ouch".